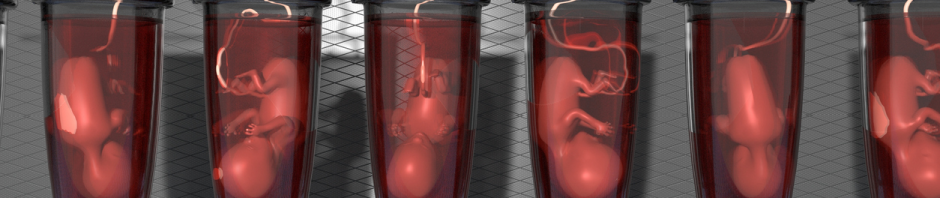

A recent article in Nature Communications announces the development of a kind of artificial womb (or extracorporeal gestational system). So far it has been used to further the development of premature lambs. Technology website Gizmodo breaks down the technical journal article in more understandable terms.

A recent article in Nature Communications announces the development of a kind of artificial womb (or extracorporeal gestational system). So far it has been used to further the development of premature lambs. Technology website Gizmodo breaks down the technical journal article in more understandable terms.

The research team, led by Alan Flake from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has shown that it’s possible to support extremely premature lambs in an external artificial womb, and to recreate the conditions required for normal gestational development. The lambs were able to grow inside a fluid-filled device, which sustained them for a record-breaking four weeks. Subsequent tests on the lambs indicated normal development of their brain, lungs, and organs. It may take another decade before this technology can be used on premature human infants, but it’s an important step in that direction.

Lambs were selected for the experiment because their lung development is in many ways similar to human lung development and thus important comparisons can be made.

There is an additional word of explanation added regarding the limits of this technology:

Importantly, the system is not meant to extend viability outside of the womb further back than 23 weeks. Nor is meant to bring a baby to full term. Rather, it’s a bridge between the mother’s womb and the outside world, supporting the infant from 23 weeks to 28 weeks of gestational age, after which time the effects of prematurity are minimal. Some scientists have speculated that eventually, we’ll able to sustain a fetus outside of the womb from the moment of conception straight through until a full term birth, but Flake stressed that their system has virtually nothing to do with this futuristic vision. “There is no technology, even on the horizon, that can support the fetus from the embryonic stage,” he said. “I would be very concerned if other parties wanted to use this device to extend viability [outside of the womb].”

The development of artificial wombs raises a host of ethical questions. Of course, this specific kind of therapeutic “bridging” technology, which would help an infant develop from 23 to 28 weeks, is largely unproblematic beyond standard questions that would arise in the development of any new intervention with premature infants (that is, questions around parental decision-making and consent, the best interests of the child, balancing the burdens and benefits of a new treatment against the benefits and burdens of present treatments, etc.).

As the article points out, however, there is a significant step if we begin to consider extracorporeal gestational systems / artificial wombs in order to gestate from conception on through the whole of pregnancy. This is why these researchers take great pains to distance themselves from the idea.

However, already other researchers are keeping embryos alive in petri dishes longer and longer. Scientists last year moved from nine days in a petri dish to 13 days. And, as reported at the time, “There’s no reason to believe that the embryos couldn’t have survived beyond the two-week mark, but the experiment had to be halted to adhere to the internationally agreed 14-day limit on human embryo research.”

Some might suggest that the idea of artificial wombs would allow us to move away from hiring women to be surrogates or might provide an alternative to abortion. However, artificial wombs would intensify issues of the commodification of human life and bring the manufacture of children to reality in a new way.

If, or perhaps we should say when, extracorporeal gestational systems are combined with gene editing technologies such as CRISPR, we could very easily be facing the prospect of the large-scale manufacture of designer children.

It is easy when faced with such a scenario to recoil and begin searching for a list of bad consequences we can hold up as a warning signal: What about the first embryos to be experimented on? What about the first children to be born this way? What will become of them if or when they develop abnormally? How many will be destroyed in the process? How long will we allow them to develop to see if abnormalities will correct themselves? There is no way to know all of the possible life-long results ahead of time. And more.

However, what’s really needed is to step back and consider the purposes of human reproduction, the idea of a child as a gift to be received and cherished rather than a product to be designed and manufactured. What are children for? What are human bodies for? Why do children come into the world in the way they do, and what is the significance of that beyond the purely mechanical/biological? As Jennifer has repeatedly said, a mother’s womb is not an arbitrary place.

It matters how children come into the world.

We err significantly if our only or if our primary ethical measure is the consequence of an action. Some things are simply right or wrong, in and of themselves, regardless of how they work out. Isn’t this one of the lessons we all learn as children, something we seek to pass on to the next generation?

May we have the wisdom to stop and think, to delve deeply into what it means to be human. And may we do so before we’ve gone so far that we are in danger of losing our very humanity.